Doomsday argument

The Doomsday argument (DA) is a probabilistic argument that claims to predict the number of future members of the human species given only an estimate of the total number of humans born so far. Simply put, it says that supposing the humans alive today are in a random place in the whole human history timeline, chances are we are about halfway through it.

It was first proposed in an explicit way by the astrophysicist Brandon Carter in 1983,[1] from which it is sometimes called the Carter catastrophe; the argument was subsequently championed by the philosopher John A. Leslie and has since been independently discovered by J. Richard Gott[2] and Holger Bech Nielsen.[3] Similar principles of eschatology were proposed earlier by Heinz von Foerster, among others.

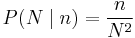

Denoting by N the total number of humans who were ever or will ever be born, the Copernican principle suggests that humans are equally likely (along with the other N − 1 humans) to find themselves at any position n, so humans assume that our fractional position f = n/N is uniformly distributed on the interval [0, 1] prior to learning our absolute position.

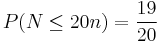

f is uniformly distributed on (0, 1] even after learning of the absolute position n. That is, for example, there is 95% chance that f is in the interval (0.05, 1], that is f > 0.05. In other words we could assume that we could be 95% certain that we would be within the last 95% of all the humans ever to be born. If we know our absolute position n, this implies an upper bound for N obtained by rearranging n/N > 0.05 to give N < 20n.

If Leslie's Figure[4] is used, then 60 billion humans have been born so far, therefore it can be estimated that there is a 95% chance that the total number of humans N will be less than 20 × 60 billion = 1.2 trillion. Assuming that the world population stabilizes at 10 billion and a life expectancy of 80 years, it can be estimated that the remaining 1140 billion humans will be born in 9120 years. Depending on the projection of world population in the forthcoming centuries, estimates may vary, but the main point of the argument is that it is unlikely that more than 1.2 trillion humans will ever live. This problem is similar to the famous German tank problem.

Aspects

Remarks

- The step that converts N into an extinction time depends upon a finite human lifespan. If immortality becomes common, and the birth rate drops to zero, then the human race could continue forever even if the total number of humans N is finite.

- A precise formulation of the Doomsday Argument requires the Bayesian interpretation of probability

- Even among Bayesians some of the assumptions of the argument's logic would not be acceptable; for instance, the fact that it is applied to a temporal phenomenon (how long something lasts) means that N's distribution simultaneously represents an "aleatory probability" (as a future event), and an "epistemic probability" (as a decided value about which we are uncertain).

- The U (0,1] f distribution is derived from two choices, which whilst being the default are also arbitrary:

- The principle of indifference, so that it is as likely for any other randomly selected person to be born after you as before you.

- The assumption of no 'prior' knowledge on the distribution of N.

Simplification: two possible total number of humans

Assume for simplicity that the total number of humans who will ever be born is 60 billion (N1), or 6,000 billion (N2).[5] If there is no prior knowledge of the position that a currently living individual, X, has in the history of humanity, we may instead compute how many humans were born before X, and arrive at (say) 59,854,795,447, which would roughly place X amongst the first 60 billion humans who have ever lived.

Now, if we assume that the number of humans who will ever be born equals N1, the probability that X is amongst the first 60 billion humans who have ever lived is of course 100%. However, if the number of humans who will ever be born equals N2, then the probability that X is amongst the first 60 billion humans who have ever lived is only 1%. Since X is in fact amongst the first 60 billion humans who have ever lived, this means that the total number of humans who will ever be born is more likely to be much closer to 60 billion than to 6,000 billion. In essence the DA therefore suggests that human extinction is more likely to occur sooner rather than later.

It is possible to sum the probabilities for each value of N and therefore to compute a statistical 'confidence limit' on N. For example, taking the numbers above, it is 99% certain that N is smaller than 6,000 billion.

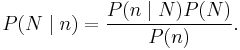

Note that as remarked above, this argument assumes that the prior probability for N is flat, or 50% for N1 and 50% for N2 in the absence of any information about X. On the other hand, it is possible to conclude, given X, that N2 is more likely than N1, if a different prior is used for N. More precisely, Bayes' theorem tells us that P(N|X)=P(X|N)P(N)/P(X), and the conservative application of the Copernican principle tells us only how to calculate P(X|N). Taking P(X) to be flat, we still have to make an assumption about the prior probability P(N) that the total number of humans is N. If we conclude that N2 is much more likely than N1 (for example, because producing a larger population takes more time, increasing the chance that a low-probability but cataclysmic natural event will take place in that time), then P(X|N) can become more heavily weighted towards the bigger value of N. A further, more detailed discussion, as well as relevant distributions P(N), are given below in the Rebuttals section.

What the argument is not

The Doomsday argument (DA) does not say that humanity cannot or will not exist indefinitely. It does not put any upper limit on the number of humans that will ever exist, nor provide a date for when humanity will become extinct.

An abbreviated form of the argument does make these claims, by confusing probability with certainty. However, the actual DA's conclusion is:

- There is a 95% chance of extinction within 9120 years.

The DA gives a 5% chance that some humans will still be alive at the end of that period. (These dates are based on the assumptions above; the precise numbers vary among specific Doomsday arguments.)

The DA does not predict the extinction of all intelligent life on Earth, only the extinction of humans.

Variations

This argument has generated a lively philosophical debate, and no consensus has yet emerged on its solution. The variants described below produce the DA by separate derivations.

Gott's formulation: 'vague prior' total population

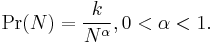

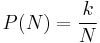

Gott specifically proposes the functional form for the prior distribution of the number of people who will ever be born (N). Gott's DA used the vague prior distribution:

.

.

where

- P(N) is the probability prior to discovering n, the total number of humans who have yet been born.

- The constant, k, is chosen to normalize the sum of P(N). The value chosen isn't important here, just the functional form (this is an improper prior, so no value of k gives a valid distribution, but Bayesian inference is still possible using it.)

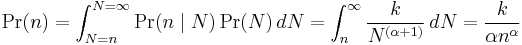

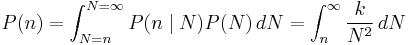

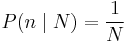

Since Gott specifies the prior distribution of total humans, P(N), Bayes's theorem and the principle of indifference alone give us P(N|n), the probability of N humans being born if n is a random draw from N:

This is Bayes's theorem for the posterior probability of total population exactly N, conditioned on current population exactly n. Now, using the indifference principle:

.

.

The unconditioned n distribution of the current population is identical to the vague prior N probability density function,[6] so:

,

,

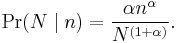

giving P (N | n) for each specific N (through a substitution into the posterior probability equation):

.

.

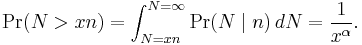

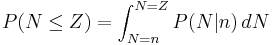

The easiest way to produce the doomsday estimate with a given confidence (say 95%) is to pretend that N is a continuous variable (since it is very large) and integrate over the probability density from N = n to N = Z. (This will give a function for the probability that N ≤ Z):

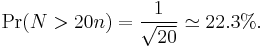

Defining Z = 20n gives:

.

.

This is the simplest Bayesian derivation of the Doomsday Argument:

- The chance that the total number of humans that will ever be born (N) is greater than twenty times the total that have been is below 5%

The use of a vague prior distribution seems well-motivated as it assumes as little knowledge as possible about N, given that any particular function must be chosen. It is equivalent to the assumption that the probability density of one's fractional position remains uniformly distributed even after learning of one's absolute position (n).

Gott's 'reference class' in his original 1993 paper was not the number of births, but the number of years 'humans' had existed as a species, which he put at 200,000. Also, Gott tried to give a 95% confidence interval between a minimum survival time and a maximum. Because of the 2.5% chance that he gives to underestimating the minimum he has only a 2.5% chance of overestimating the maximum. This equates to 97.5% confidence that extinction occurs before the upper boundary of his confidence interval.

97.5% is one chance in forty, which can be used in the integral above with Z = 40n, and n = 200,000 years:

This is how Gott produces a 97.5% confidence of extinction within N ≤ 8,000,000 years. The number he quoted was the likely time remaining, N − n = 7.8 million years. This was much higher than the temporal confidence bound produced by counting births, because it applied the principle of indifference to time. (Producing different estimates by sampling different parameters in the same hypothesis is Bertrand's paradox.)

His choice of 95% confidence bounds (rather than 80% or 99.9%, say) matched the scientifically accepted limit of statistical significance for hypothesis rejection. Therefore, he argued that the hypothesis: “humanity will cease to exist before 5,100 years or thrive beyond 7.8 million years” can be rejected.

Leslie's argument differs from Gott's version in that he does not assume a vague prior probability distribution for N. Instead he argues that the force of the Doomsday Argument resides purely in the increased probability of an early Doomsday once you take into account your birth position, regardless of your prior probability distribution for N. He calls this the probability shift.

Heinz von Foerster argued that humanity's abilities to construct societies, civilizations and technologies do not result in self inhibition. Rather, societies' success varies directly with population size. Von Foerster found that this model fit some 25 data points from the birth of Jesus to 1958, with only 7% of the variance left unexplained. Several follow-up letters (1961, 1962, …) were published in Science showing that von Foerster's equation was still on track. The data continued to fit up until 1973. The most remarkable thing about von Foerster's model was it predicted that the human population would reach infinity or a mathematical singularity, on Friday, November 13, 2026. In fact, von Foerster did not imply that the world population on that day could actually become infinite. The real implication was that the world population growth pattern followed for many centuries prior to 1960 was about to come to an end and be transformed into a radically different pattern. Note that this prediction began to be fulfilled just in a few years after the "Doomsday" was published.[7]

Reference classes

One of the major areas of Doomsday Argument debate is the reference class from which n is drawn, and of which N is the ultimate size. The 'standard' Doomsday Argument hypothesis doesn't spend very much time on this point, and simply says that the reference class is the number of 'humans'. Given that you are human, the Copernican principle could be applied to ask if you were born unusually early, but the grouping of 'human' has been widely challenged on practical and philosophical grounds. Nick Bostrom has argued that consciousness is (part of) the discriminator between what is in and what is out of the reference class, and that extraterrestrial intelligences might affect the calculation dramatically.

The following sub-sections relate to different suggested reference classes, each of which has had the standard Doomsday Argument applied to it.

Sampling only WMD-era humans

The Doomsday clock shows the expected time to nuclear doomsday by the judgment of an expert board, rather than a Bayesian model. If the twelve hours of the clock symbolize the lifespan of the human species, its current time of 11:54 implies that we are among the last 1% of people who will ever be born (i.e. that n > 0.99N). J. Richard Gott's temporal version of the Doomsday argument (DA) would require very strong prior evidence to overcome the improbability of being born in such a special time.

- If the clock's doomsday estimate is correct, there is less than 1 chance in 100 of seeing it show such a late time in human history, if observed at a random time within that history.

The scientists' warning can be reconciled with the DA, however: The Doomsday clock specifically estimates the proximity of atomic self-destruction—which has only been possible for sixty years.[8] If doomsday requires nuclear weaponry then the Doomsday Argument 'reference class' is: people contemporaneous with nuclear weapons. In this model, the number of people living through, or born after Hiroshima is n, and the number of people who ever will is N. Applying Gott's DA to these variable definitions gives a 50% chance of doomsday within 50 years.

- In this model, the clock's hands are so close to midnight because a condition of doomsday is living post-1945, a condition which applies now but not to the earlier 11 hours and 53 minutes of the clock's metaphorical human 'day'.

If your life is randomly selected from all lives lived under the shadow of the bomb, this simple model gives a 95% chance of doomsday within 1000 years.

The scientists' recent use of moving the clock forward to warn of the dangers posed by global warming muddles this reasoning, however.

SSSA: Sampling from observer-moments

Nick Bostrom, considering observation selection effects, has produced a Self-Sampling Assumption (SSA): "that you should think of yourself as if you were a random observer from a suitable reference class". If the 'reference class' is the set of humans to ever be born, this gives N < 20n with 95% confidence (the standard Doomsday argument). However, he has refined this idea to apply to observer-moments rather than just observers. He has formalized this ([1] as:

- The Strong Self-Sampling Assumption (SSSA): Each observer-moment should reason as if it were randomly selected from the class of all observer-moments in its reference class.

If the minute in which you read this article is randomly selected from every minute in every human's lifespan then (with 95% confidence) this event has occurred after the first 5% of human observer-moments. If the mean lifespan in the future is twice the historic mean lifespan, this implies 95% confidence that N < 10n (the average future human will account for twice the observer-moments of the average historic human). Therefore, the 95th percentile extinction-time estimate in this version is 4560 years.

Rebuttals

We are in the earliest 5%, a priori

If you agree with the statistical methods, still disagreeing with the Doomsday argument (DA) implies that:

- We are within the first 5% of humans to be born.

- This is not purely a coincidence.

Therefore, these rebuttals try to give reasons for believing that we are some of the earliest humans.

For instance, you are member 50,000 in a collaborative project, the Doomsday Argument implies a 95% chance that there will never be more than a million members of that project. This can be refuted if your other characteristics are typical of the early adopter. The mainstream of potential users will prefer to be involved when the project is nearly complete. If you enjoy the project's incompleteness, we already know that you are unusual, prior to the discovery of your early involvement.

If you have measurable attributes that set you apart from the typical long run user, the project DA can be refuted based on the fact that you would expect to be within the first 5% of members, a priori. The analogy to the total-human-population form of the argument is: Confidence in a prediction of the distribution of human characteristics that places modern & historic humans outside the mainstream, implies that we already know, before examining n that it is likely to be very early in N.

For example, if you are certain that 99% of humans who will ever live will be cyborgs, but that only a negligible fraction of humans who have been born to date are cyborgs, you could be equally certain that at least one hundred times as many people remain to be born as have been.

Robin Hanson's paper sums up these criticisms of the DA:

- "All else is not equal; we have good reasons for thinking we are not randomly selected humans from all who will ever live."

Drawbacks of this rebuttal:

- The question of how the confident prediction is derived. We need an uncannily prescient picture of humanity's statistical distribution through all time, before we can pronounce ourselves extreme members of that population. (In contrast, project pioneers have clearly distinct psychology from the mainstream.)

- If the majority of humans have characteristics we do not share, some would argue that this is equivalent to the Doomsday argument, since people like us will become extinct.

Critique: Human extinction is distant, a posteriori

The a posteriori observation that extinction level events are rare could be offered as evidence that the DA's predictions are implausible; typically, extinctions of a dominant species happens less often than once in a million years. Therefore, it is argued that Human extinction is unlikely within the next ten millennia. (Another probabilistic argument, drawing a different conclusion from the DA.)

In Bayesian terms, this response to the DA says that our knowledge of history (or ability to prevent disaster) produces a prior marginal for N with a minimum value in the trillions. If N is distributed uniformly from 1012 to 1013, for example, then the probability of N < 1,200 billion inferred from n = 60 billion will be extremely small. This is an equally impeccable Bayesian calculation, rejecting the Copernican principle on the grounds that we must be 'special observers' since there is no likely mechanism for humanity to go extinct within the next hundred thousand years.

This response is accused of overlooking the technological threats to humanity's survival, to which earlier life was not subject, and is specifically rejected by most of the DA's academic critics (arguably excepting Robin Hanson).

In fact, many futurologists believe the empirical situation is worse than Gott's DA estimate. For instance, Sir Martin Rees believes that the technological dangers give an estimated human survival duration of ninety-five years (with 50% confidence.) Earlier prophets made similar predictions and were 'proven' wrong (e.g. on surviving the nuclear arms race). It is possible that their estimates were accurate, and that their common image as alarmists is a survivorship bias.

The prior N distribution may make n very uninformative

Robin Hanson argues that N's prior may be exponentially distributed:

Here, c and q are constants. If q is large, then our 95% confidence upper bound is on the uniform draw, not the exponential value of N.

The best way to compare this with Gott's Bayesian argument is to flatten the distribution from the vague prior by having the probability fall off more slowly with N (than inverse proportionally). This corresponds to the idea that humanity's growth may be exponential in time with doomsday having a vague prior pdf in time. This would mean than N, the last birth, would have a distribution looking like the following:

This prior N distribution is all that is required (with the principle of indifference) to produce the inference of N from n, and this is done in an identical way to the standard case, as described by Gott (equivalent to  = 1 in this distribution):

= 1 in this distribution):

Substituting into the posterior probability equation):

Integrating the probability of any N above xn:

For example, if x = 20, and  = 0.5, this becomes:

= 0.5, this becomes:

Therefore, with this prior, the chance of a trillion births is well over 20%, rather than the 5% chance given by the standard DA. If  is reduced further by assuming a flatter prior N distribution, then the limits on N given by n become weaker. An

is reduced further by assuming a flatter prior N distribution, then the limits on N given by n become weaker. An  of one reproduces Gott's calculation with a birth reference class, and

of one reproduces Gott's calculation with a birth reference class, and  around 0.5 could approximate his temporal confidence interval calculation (if the population were expanding exponentially). As

around 0.5 could approximate his temporal confidence interval calculation (if the population were expanding exponentially). As  (gets smaller) n becomes less and less informative about N. In the limit this distribution approaches an (unbounded) uniform distribution, where all values of N are equally likely. This is Page et al.'s "Assumption 3", which they find few reasons to reject, a priori. (Although all distributions with

(gets smaller) n becomes less and less informative about N. In the limit this distribution approaches an (unbounded) uniform distribution, where all values of N are equally likely. This is Page et al.'s "Assumption 3", which they find few reasons to reject, a priori. (Although all distributions with  are improper priors, this applies to Gott's vague-prior distribution also, and they can all be converted to produce proper integrals by postulating a finite upper population limit.) Since the probability of reaching a population of size 2N is usually thought of as the chance of reaching N multiplied by the survival probability from N to 2N it seems that Pr(N) must be a monotonically decreasing function of N, but this doesn't necessarily require an inverse proportionality.

are improper priors, this applies to Gott's vague-prior distribution also, and they can all be converted to produce proper integrals by postulating a finite upper population limit.) Since the probability of reaching a population of size 2N is usually thought of as the chance of reaching N multiplied by the survival probability from N to 2N it seems that Pr(N) must be a monotonically decreasing function of N, but this doesn't necessarily require an inverse proportionality.

A prior distribution with a very low  parameter makes the DA's ability to constrain the ultimate size of humanity very weak.

parameter makes the DA's ability to constrain the ultimate size of humanity very weak.

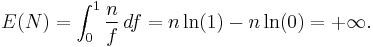

Infinite Expectation

Another objection to the Doomsday Argument is that the expected total human population is actually infinite. The calculation is as follows:

- The total human population N = n/f, where n is the human population to date and f is our fractional position in the total.

- We assume that f is uniformly distributed on (0,1].

- The expectation of N is

This infinite expectation shows that, under the framework of the DA, humanity still has some chance of surviving an arbitrarily long time.

For a similar example of counterintuitive infinite expectations, see the St. Petersburg paradox.

SIA: The possibility of not existing at all

One objection is that the possibility of your existing at all depends on how many humans will ever exist (N). If this is a high number, then the possibility of your existing is higher than if only a few humans will ever exist. Since you do indeed exist, this is evidence that the number of humans that will ever exist is high.

This objection, originally by Dennis Dieks (1992), is now known by Nick Bostrom's name for it: the "Self-Indication Assumption objection". It can be shown that some SIAs prevent any inference of N from n (the current population); for details of this argument from the Bayesian inference perspective see: Self-Indication Assumption Doomsday argument rebuttal.

Caves' rebuttal

The Bayesian argument by Carlton M. Caves says that the uniform distribution assumption is incompatible with the Copernican principle, not a consequence of it.

He gives a number of examples to argue that Gott's rule is implausible. For instance, he says, imagine stumbling into a birthday party, about which you know nothing:

Your friendly enquiry about the age of the celebrant elicits the reply that she is celebrating her (tp = ) 50th birthday. According to Gott, you can predict with 95% confidence that the woman will survive between [50]/39 = 1.28 years and 39[×50] = 1,950 years into the future. Since the wide range encompasses reasonable expectations regarding the woman's survival, it might not seem so bad, till one realizes that [Gott's rule] predicts that with probability 1/2 the woman will survive beyond 100 years old and with probability 1/3 beyond 150. Few of us would want to bet on the woman's survival using Gott's rule. (See Caves' online paper below.)

Although this example exposes a weakness in J. Richard Gott's "Copernicus method" DA (that he does not specify when the "Copernicus method" can be applied) it is not precisely analogous with the modern DA; epistemological refinements of Gott's argument by philosophers such as Nick Bostrom specify that:

- Knowing the absolute birth rank (n) must give no information on the total population (N).

Careful DA variants specified with this rule aren't shown implausible by Caves' "Old Lady" example above, because, the woman's age is given prior to the estimate of her lifespan. Since human age gives an estimate of survival time (via actuarial tables) Caves' Birthday party age-estimate could not fall into the class of DA problems defined with this proviso.

To produce a comparable "Birthday party example" of the carefully specified Bayesian DA we would need to completely exclude all prior knowledge of likely human life spans; in principle this could be done (e.g.: hypothetical Amnesia chamber). However, this would remove the modified example from everyday experience. To keep it in the everyday realm the lady's age must be hidden prior to the survival estimate being made. (Although this is no longer exactly the DA, it is much more comparable to it.)

Without knowing the lady’s age, the DA reasoning produces a rule to convert the birthday (n) into a maximum lifespan with 50% confidence (N). Gott's Copernicus method rule is simply: Prob (N < 2n) = 50%. How accurate would this estimate turn out to be? Western demographics are now fairly uniform across ages, so a random birthday (n) could be (very roughly) approximated by a U(0,M] draw where M is the maximum lifespan in the census. In this 'flat' model, everyone shares the same lifespan so N = M. If n happens to be less than (M)/2 then Gott's 2n estimate of N will be under M, its true figure. The other half of the time 2n underestimates M, and in this case (the one Caves highlights in his example) the subject will die before the 2n estimate is reached. In this 'flat demographics' model Gott's 50% confidence figure is proven right 50% of the time.

Self-referencing doomsday argument rebuttal

Some philosophers have been bold enough to suggest that only people who have contemplated the Doomsday argument (DA) belong in the reference class 'human'. If that is the appropriate reference class, Carter defied his own prediction when he first described the argument (to the Royal Society). A member present could have argued thus:

Presently, only one person in the world understands the Doomsday argument, so by its own logic there is a 95% chance that it is a minor problem which will only ever interest twenty people, and I should ignore it.

Jeff Dewynne and Professor Peter Landsberg suggested that this line of reasoning will create a paradox for the Doomsday argument:

If a member did pass such a comment, it would indicate that they understood the DA sufficiently well that in fact 2 people could be considered to understand it, and thus there would a 5% chance that 40 or more people would actually be interested. Also, of course, ignoring something because you only expect a small number of people to be interested in it is extremely short sighted—if this approach were to be taken, nothing new would ever be explored, if we assume no a priori knowledge of the nature of interest and attentional mechanisms.

Additionally, it should be considered that because Carter did present and describe his argument, in which case the people to whom he explained it did contemplate the DA, as it was inevitable, the conclusion could then be drawn that in the moment of explanation Carter created the basis for his own prediction.

Conflation of future duration with total duration

A rebuttal by Ronald Pisaturo in 2009[9] argues that the Doomsday Argument conflates future duration and total duration.

According to Pisaturo, the Doomsday Argument relies on the equivalent of this equation:

![P(H_{TS}|D_pX)/P(H_{TL}|D_pX) = [P(H_{FS}|X)/P(H_{FL}|X)] \cdot [P(D_p|H_{TS}X)/P(D_p|H_{TL}X)]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/cc007ecd0f1439e1192015f5e89fdd06.png) ,

,- where:

- X = the prior information;

- Dp = the data that past duration is tp;

- HFS = the hypothesis that the future duration of the phenomenon will be short;

- HFL = the hypothesis that the future duration of the phenomenon will be long;

- HTS = the hypothesis that the total duration of the phenomenon will be short—i.e., that tt, the phenomenon’s total longevity, = tTS;

- HTL = the hypothesis that the total duration of the phenomenon will be long—i.e., that tt, the phenomenon’s total longevity, = tTL, with tTL > tTS.

Pisaturo then observes:

- Clearly, this is an invalid application of Bayes’ theorem, as it conflates future duration and total duration.

Pisaturo takes numerical examples based on two possible corrections to this equation: considering only future durations, and considering only total durations. In both cases, he concludes that the Doomsday Argument’s claim, that there is a ‘Bayesian shift’ in favor of the shorter future duration, is fallacious.

Mathematics-free explanation by analogy

Assume the human species is a car driver. The driver has encountered some bumps but no catastrophes, and the car (Earth) is still road-worthy. However, insurance is required. The cosmic insurer has not dealt with humanity before, and needs some basis on which to calculate the premium. According to the Doomsday Argument, the insurer merely need ask how long the car and driver have been on the road—currently at least 40,000 years without an "accident"—and use the response to calculate insurance based on a 50% chance that a fatal "accident" will occur inside that time period.

Consider a hypothetical insurance company that tries to attract drivers with long accident-free histories not because they necessarily drive more safely than newly qualified drivers, but for statistical reasons: the hypothetical insurer estimates that each driver looks for insurance quotes every year, so that the time since the last accident is an evenly distributed random sample between accidents. The chance of being more than halfway through an evenly distributed random sample is one-half, and (ignoring old-age effects) if the driver is more than half way between accidents then they are closer to their next accident than their previous one. A driver who was accident-free for 10 years would be quoted a very low premium for this reason, but someone should not expect cheap insurance if they only passed their test two hours ago (equivalent to the accident-free record of the human species in relation to 40,000 years of geological time.)

Analogy to the estimated final score of a cricket batsman

A random in-progress cricket test match is sampled for a single piece of information: the current batsman's run tally so far. If the batsman is dismissed (rather than declaring), what is the chance that he will end up with a score more than double his current total?

- A rough empirical result is that the chance is half (on average).

The Doomsday argument (DA) is that even if we were completely ignorant of the game we could make the same prediction, or profit by offering a bet paying odds of 2-to-3 on the batsmen doubling his current score.

Importantly, we can only offer the bet before the current score is given (this is necessary because the absolute value of the current score would give a cricket expert a lot of information about the chance of that tally doubling). It is necessary to be ignorant of the absolute run tally before making the prediction because this is linked to the likely total, but if the likely total and absolute value are not linked the survival prediction can be made after discovering the batter's current score. Analogously, the DA says that if the absolute number of humans born gives no information on the number that will be, we can predict the species’ total number of births after discovering that 60 billion people have ever been born: with 50% confidence it is 120 billion people, so that there is better-chance-than-not that the last human birth will occur before the 23rd century.

It is not true that the chance is half, whatever is the number of runs currently scored; batting records give an empirical correlation between reaching a given score (50 say) and reaching any other, higher score (say 100). On the average, the chance of doubling the current tally may be half, but the chance of reaching a century having scored fifty is much lower than reaching ten from five. Thus, the absolute value of the score gives information about the likely final total the batsman will reach, beyond the “scale invariant”.[10]

An analogous Bayesian critique of the DA is that is somehow possessed prior knowledge of the all-time human population distribution (total runs scored), and that this is more significant than the finding of a low number of births until now (a low current run count).

There are two alternative methods of making uniform draws from the current score (n):

- Put the runs actually scored by dismissed player in order, say 200, and randomly choose between these scoring increments by U(0, 200].

- Select a time randomly from the beginning of the match to the final dismissal.

The second sampling-scheme will include those lengthy periods of a game where a dismissed player is replaced, during which the ‘current batsman’ is preparing to take the field and has no runs. If people sample based on time-of-day rather than running-score they will often find that a new batsman has a score of zero when the total score that day was low, but humans will rarely sample a zero if one batsman stayed at the crease, piling on runs all day long. Therefore, the fact that sampling a non-zero score would tell us something about the likely final score that the current batsman will achieve.

Choosing sampling method 2 rather than method 1 would give a different statistical link between current and final score: any non-zero score would imply that the batsman reached a high final total, especially if the time to replace batsman is very long. This is analogous to the SIA-DA-refutation that N's distribution should include N = 0 states, which leads to the DA having reduced predictive power (in the extreme, no power to predict N from n at all).

See also

- Doomsday

- Doomsday events

- Fermi paradox

- Final anthropic principle

- Hypothetical disasters

- Mediocrity principle

- Quantum immortality

- Simulated reality

- Sic transit gloria mundi

- Survival analysis

- Survivalism

- Technological singularity

Notes

- ^ Brandon Carter; McCrea, W. H. (1983). "The anthropic principle and its implications for biological evolution". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A310 (1512): 347–363. doi:10.1098/rsta.1983.0096.

- ^ J. Richard Gott, III (1993). "Implications of the Copernican principle for our future prospects". Nature 363 (6427): 315–319. doi:10.1038/363315a0.

- ^ Holger Bech Nielsen (1989). "Random dynamics and relations between the number of fermion generations and the fine structure constants". Acta Physica Polonica B20: 427–468.

- ^ http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.49.5899&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- ^ Doomsday argument two-case section is partially based on a refutation of the Doomsday Argument by Korb and Oliver.

- ^ The only probability density functions that must be specified a priori are:

- Pr(N) - the ultimate number of people that will be born, assumed by J. Richard Gott to have a vague prior distribution, Pr(N) = k/N

- Pr(n|N) - the chance of being born in any position based on a total population N - all DA forms assume the Copernican principle, making Pr(n|N) = 1/N

- ^ See, for example, Introduction to Social Macrodynamics by Andrey Korotayev et al.

- ^ The clock first appeared in 1949, and the date on which humanity gained the power to destroy itself is debatable, but to simplify the argument the numbers here are based on an assumption of fifty years.

- ^ Ronald Pisaturo (2009). "Past Longevity as Evidence for the Future". Philosophy of Science 76: 73–100. doi:10.1086/599273.

- ^ The cricketing rationale for the lengthening of future survival time with current score is that batting is a test of skill that a high-scoring batsman has passed. Therefore, higher scores are correlated with better players who will then be more likely to continue scoring heavily. Historic batting records give a prior distribution that provides other useful data. In particular, we know the mean score across all players and matches. High and low posterior information (the current score) only gives a weak indication of the player's skill, which is more strongly described by this prior mean. (This statistical phenomenon of informative averages is called Regression toward the mean.)

References

- John Leslie, The End of the World: The Science and Ethics of Human Extinction, Routledge, 1998, ISBN 0-415-18447-9.

- J. R. Gott III, Future Prospects Discussed, Nature, vol. 368, p. 108, 1994.

- This argument plays a central role in Stephen Baxter's science fiction book, Manifold: Time, Del Rey Books, 2000, ISBN 0-345-43076-X.

External links

- A non-mathematical, unpartisan introduction to the DA

- A compelling lecture from the University of Colorado-Boulder

- Nick Bostrom's response to Korb and Oliver

- Nick Bostrom's summary version of the argument

- Nick Bostrom's annotated collection of references

- Kopf, Krtouš & Page's early (1994) refutation based on the SIA, which they called "Assumption 2".

- The Doomsday argument and the number of possible observers by Ken Olum In 1993 J. Richard Gott used his "Copernicus method" to predict the lifetime of Broadway shows. One part of this paper uses the same reference class as an empirical counter-example to Gott's method.

- A Critique of the Doomsday Argument by Robin Hanson

- A Third Route to the Doomsday Argument by Paul Franceschi, Journal of Philosophical Research, 2009, vol. 34, pp. 263–278

- Chambers' Ussherian Corollary Objection

- Caves' Bayesian critique of Gott's argument. C. M. Caves, "Predicting future duration from present age: A critical assessment", Contemporary Physics 41, 143-153 (2000).

- C.M. Caves, "Predicting future duration from present age: Revisiting a critical assessment of Gott's rule.

- "Infinitely Long Afterlives and the Doomsday Argument" by John Leslie shows that Leslie has recently modified his analysis and conclusion (Philosophy 83 (4) 2008 pp. 519–524): Abstract -- A recent book of mine defends three distinct varieties of immortality. One of them is an infinitely lengthy afterlife; however, any hopes of it might seem destroyed by something like Brandon Carter's ‘doomsday argument’ against viewing ourselves as extremely early humans. The apparent difficulty might be overcome in two ways. First, if the world is non-deterministic then anything on the lines of the doomsday argument may prove unable to deliver a strongly pessimistic conclusion. Secondly, anything on those lines may break down when an infinite sequence of experiences is in question.

- Mark Greenberg, "Apocalypse Not Just Now" in London Review of Books

- Laster: A simple webpage applet giving the min & max survival times of anything with 50% and 95% confidence requiring only that you input how old it is. It is designed to use the same mathematics as J. Richard Gott's form of the DA, and was programmed by sustainable development researcher Jerrad Pierce.

|

|||||

![P(N \leq 40[200000]) = \frac{39}{40}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/47618d63ae4ed64da6933daa6a537668.png)

![N = \frac{e^{U(0, q]}}{c}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/57e64b6560d3b6d2a95cbc80d931c266.png)